Frank Horvat Italian, 28/04/1928-21/10/2020

Printed later.

.

76.5 x 50.5 cm / 30 1/8 x 19 7/8 in

.

Edition of 30

35.5 x 23.5 cm / 14 x 9 1/4 in

.

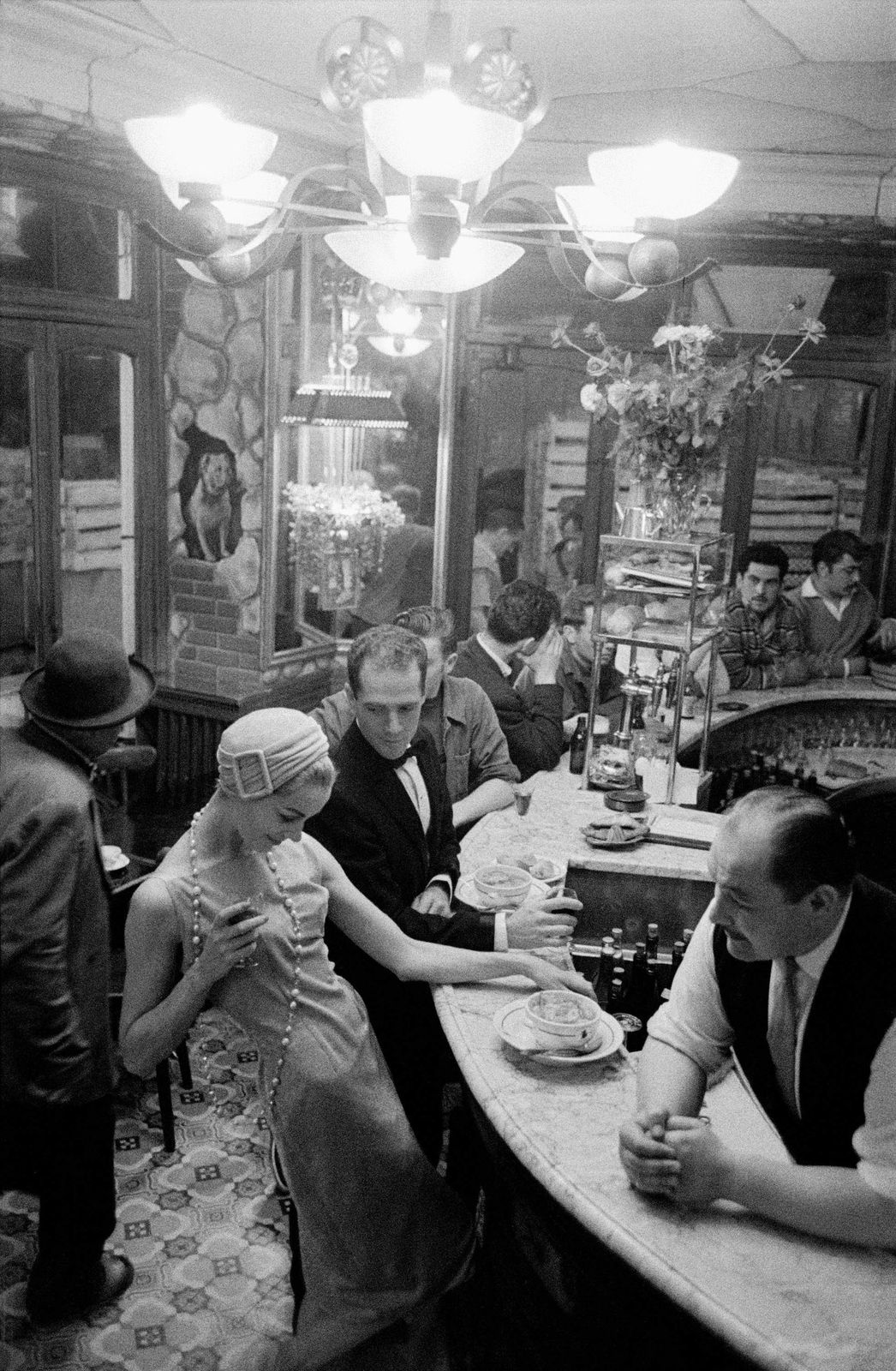

Frank Horvat's 1957 photograph of model Tan Arnold at Au Chien qui Fume represents a decisive rupture in fashion photography's relationship with reality. Commissioned by Jardin des Modes during Horvat's transition from photojournalism, this image refuses the studio's hermetic control, placing its model within Paris's authentic social fabric.

The restaurant—operating since 1740, frequented by Les Halles market workers—becomes more than backdrop; it's archaeological evidence of Parisian life made visible. Yet Horvat understood photography's essential paradox: the more "real" the setting, the more constructed the image becomes. Arnold's presence among genuine patrons creates irreducible theatrical tension—she belongs and doesn't belong simultaneously.

His technical choices amplify this contradiction. The telephoto lens compresses space, creating intimacy while maintaining voyeuristic distance. The result feels both documentary and fictional, authentic yet utterly performed. Multiple narrative layers unfold: ornate Belle Époque fixtures, reflected surfaces multiplying space, animated patron gestures—what we might call "a moment thick with accumulated time."

This photograph anticipates fashion imagery where authenticity becomes performance. Horvat grasped that fashion photography's power lies not in displaying garments but in constructing desire through narrative complexity. The model transforms into actress, restaurant into stage, photograph into compressed cinema.

The image's enduring influence stems from recognizing that all photography is inherently performative. By embracing rather than disguising this condition, Horvat created work that feels simultaneously of its historical moment and strangely prophetic. In placing fashion within quotidian reality, he revealed both as fundamentally constructed experiences.

Today, when authentic experience is perpetually mediated, Horvat's photograph reads as remarkably prescient, suggesting photography's deepest truth lies not in illusory transparency but in acknowledging its sophisticated mechanisms of construction and desire.