Louis Faurer American, 1916-2001

-

Philadelphia, 1937.

Philadelphia, 1937. -

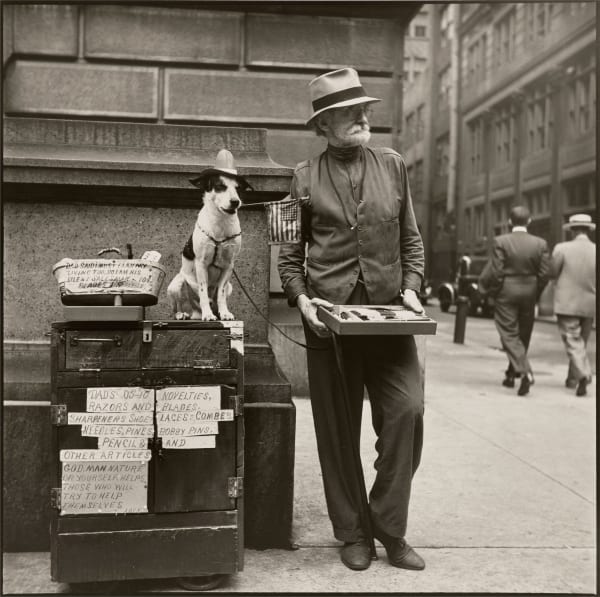

Silent Salesman, Philadelphia, 1937.

Silent Salesman, Philadelphia, 1937. -

Ideal Theatre, Philadelphia, 1938.

Ideal Theatre, Philadelphia, 1938. -

Staten Island Ferry, New York, 1946.

Staten Island Ferry, New York, 1946. -

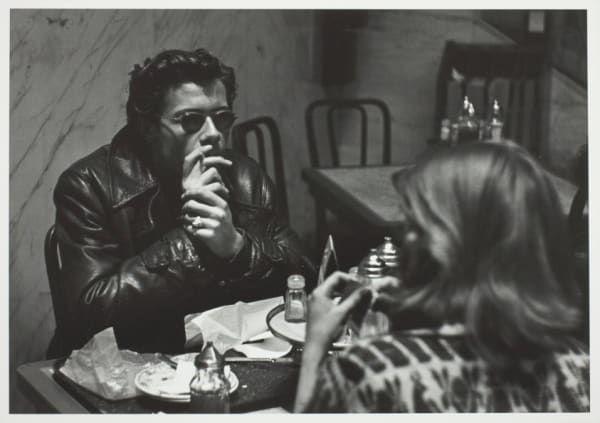

Longchamps Restaurant, 42nd and Lexington Avenue, New York City, 1946.

Longchamps Restaurant, 42nd and Lexington Avenue, New York City, 1946. -

Self-portrait, 42nd Street and 3rd Avenue El Station Looking Toward Tudor City, New York, 1946.

Self-portrait, 42nd Street and 3rd Avenue El Station Looking Toward Tudor City, New York, 1946. -

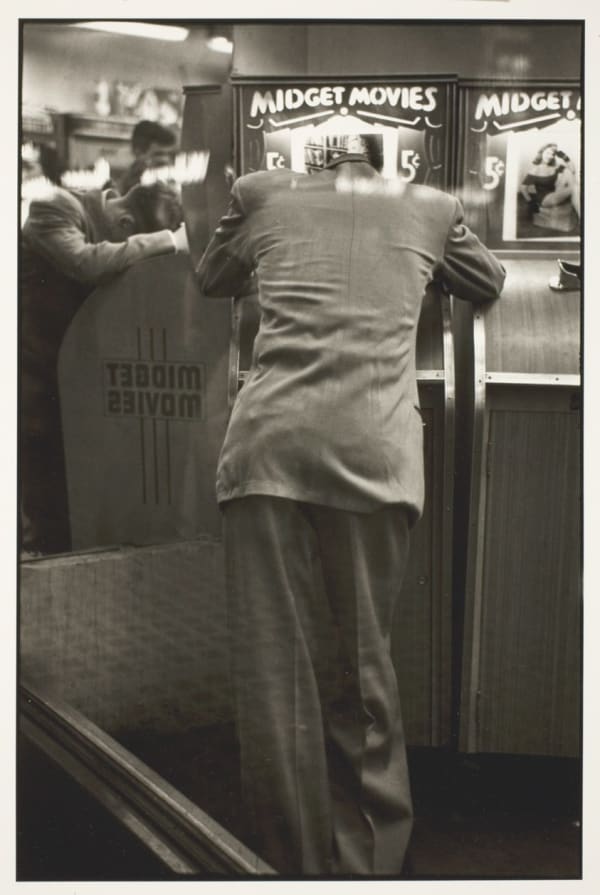

14th Street, Horn & Hardart, New York City, 1947.

14th Street, Horn & Hardart, New York City, 1947. -

New York City, 1947.

New York City, 1947. -

Playground, New York City, 1947.

Playground, New York City, 1947. -

Win, Place, and Show (3rd Avenue El), New York City, 1947.

Win, Place, and Show (3rd Avenue El), New York City, 1947. -

New York City, 1947.

New York City, 1947. -

New York City, 1947.

New York City, 1947. -

42nd Street, New York City, 1948.

42nd Street, New York City, 1948. -

Eddie, New York City, 1948.

Eddie, New York City, 1948. -

New York City, 1948.

New York City, 1948. -

Freudian Hand Clasp, New York City, 1948.

Freudian Hand Clasp, New York City, 1948. -

Orchard Street, New York City, 1948.

Orchard Street, New York City, 1948. -

Union Square, New York City, 1948.

Union Square, New York City, 1948. -

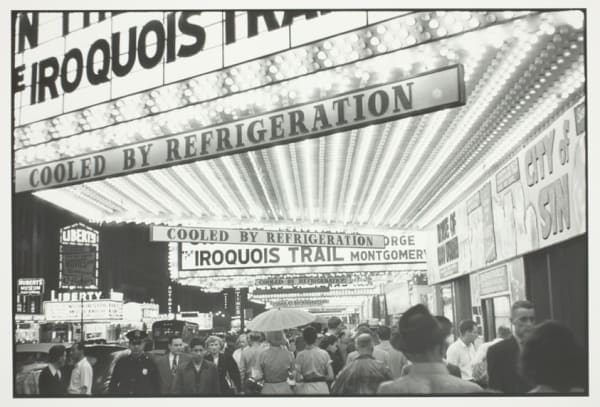

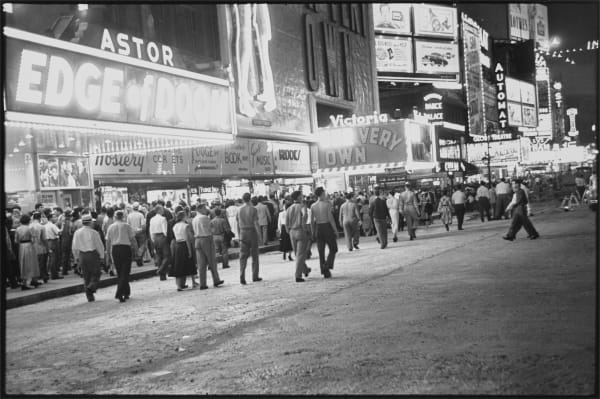

Times Square, New York, NY, 1948.

Times Square, New York, NY, 1948. -

Indian Summer New York City, 1949.

Indian Summer New York City, 1949. -

Untitled, Philadelphia, PA, 1949.

Untitled, Philadelphia, PA, 1949. -

Rat Race, New York City, 1949.

Rat Race, New York City, 1949. -

Repaving Times Square, New York City, 1949.

Repaving Times Square, New York City, 1949. -

Untitled, New York City (woman stroking man's head), 1949.

Untitled, New York City (woman stroking man's head), 1949. -

New York City, NY, (women in front of billboard), 1949.

New York City, NY, (women in front of billboard), 1949. -

New York, New York, 1949.

New York, New York, 1949. -

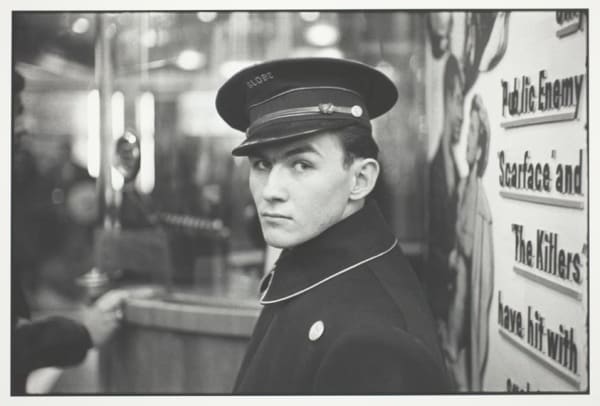

Globe Theatre, New York City, 1950.

Globe Theatre, New York City, 1950. -

Untitled, New York City (four men with cab door), 1950.

Untitled, New York City (four men with cab door), 1950. -

San Genaro Festival, New York City, 1950.

San Genaro Festival, New York City, 1950. -

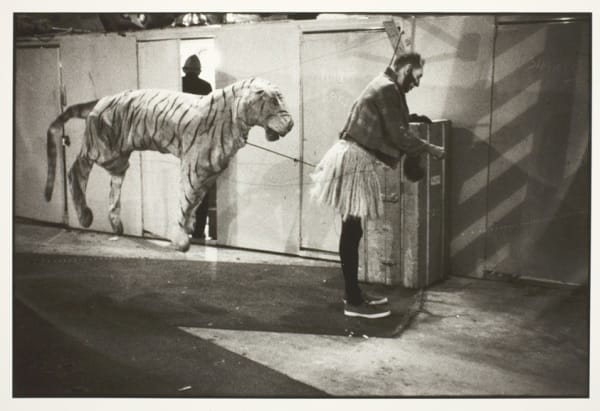

Barnun & Bailey, Circus Performers, Old Madison Square Garden, New York, NY, 1950.

Barnun & Bailey, Circus Performers, Old Madison Square Garden, New York, NY, 1950. -

Bus number 7, New York, 1950.

Bus number 7, New York, 1950. -

Untitled, NYC, (three girls in black car - joyride), 1950.

Untitled, NYC, (three girls in black car - joyride), 1950. -

Times Square USA, (Home of the Brave), 1950.

Times Square USA, (Home of the Brave), 1950. -

Barnum and Bailey Dressing Rooms, New York City, 1950.

Barnum and Bailey Dressing Rooms, New York City, 1950. -

Social Patron, New York City, 1951.

Social Patron, New York City, 1951. -

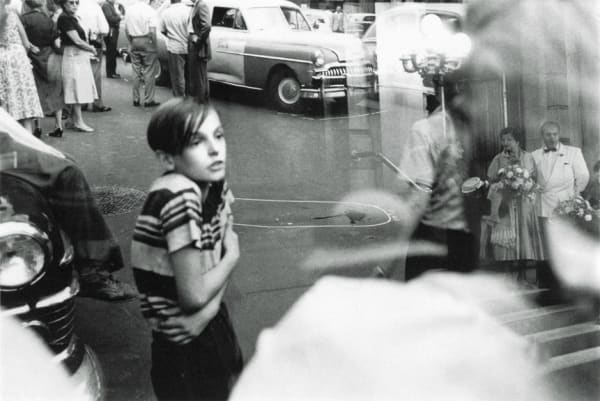

Accident, New York City, 1952.

Accident, New York City, 1952. -

Untitled, New York City, (woman reading on subway), 1973.

Untitled, New York City, (woman reading on subway), 1973.

-

Inheriting Dreams: the living legacy of photography

Gaspar Keri, Punkt, 13 October 2025 -

Inheriting Dreams

Christian Caujolle, The Eye of Photography, 30 September 2025 -

Yesterday's photographs are today's world

Ianko López, El País Semanal, 14 September 2025 -

Max Saula: Heir to a vision

Rafael Lozano, La Vanguardia, 7 September 2025

Louis Faurer (August 28, 1916 – March 2, 2001) was an American photographer whose haunting images of mid-20th-century urban life established him as one of the most psychologically penetrating documentarians of his era. Born in Philadelphia to Polish immigrant parents, Faurer emerged as a central figure in what came to be known as the New York School of photography, creating work that bridged the documentary tradition of Walker Evans and the more personal, introspective vision that would later define Robert Frank's revolutionary "The Americans".

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Faurer's artistic journey began with illustration and design, studying at the School of Commercial Art and Lettering in Philadelphia and spending summers drawing caricatures on the Atlantic City Boardwalk. His transformation into a photographer occurred in 1937 when he purchased his first camera, a used 35mm Kodak Vollenda, from his friend Ben Somoroff, who would later become one of the preeminent still life photographers of the twentieth century. This pivotal moment marked the beginning of a career that would span over four decades.

The young Faurer quickly demonstrated his natural eye for photography, winning first prize in the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger's "photo of the week" contest shortly after acquiring his camera. He began documenting life on Philadelphia's Market Street, developing the signature techniques that would later define his mature work: capturing details drawn from crowds, often refracted through shop windows or silhouetted against theater hoardings.

War Years and Technical Mastery

During World War II, Faurer served as a civilian photographer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in Philadelphia, a position that proved crucial to his artistic development. Never having photographed an actual battlefield, he nonetheless perfected his printing techniques during this period and began to understand how war's social and psychological impact manifested in civilian life. This experience would later inform his ability to capture the human condition in postwar New York, where he documented both survivors recovering from extreme injuries and the visible increase in wealth associated with the postwar boom.

New York: The Defining Chapter

Faurer's move to New York in 1947 represented the most important journey of his artistic life. There he quickly established himself within the city's vibrant photographic community, forming a particularly close friendship with Robert Frank, with whom he shared a darkroom and studio space. Walker Evans, whom Faurer had long admired, introduced him to Alexander Liberman at Vogue, facilitating his entry into the world of fashion photography.

The photographer found his true calling in the streets of Manhattan, particularly in Times Square and along 14th Street, where he gathered what the Metropolitan Museum of Art described as "a motley cast of unglamorous and marginal characters". Between 1946 and 1951, Faurer built his professional career while working intensively on his personal photography, walking the city at all hours and finding endless subjects to photograph.

As Robert Frank observed in 1994: "Faurer... proves to be an extraordinary artist. His eye is on the pulse of New York City - the lonely Times-Square people for whom Faurer felt a deep sympathy. Every photograph is witness to the compassion and obsession accompanying his life like a shadow". Frank's assessment captures the essence of Faurer's approach: his images revealed not just the external reality of urban life, but its psychological undercurrents.

Photographic Philosophy and Technique

Faurer's work was distinguished by his profound philosophical approach to photography. "My eyes search for people who are grateful for life, people who forgive whose doubts have been removed, who understand the truth, whose enduring spirit is bathed by such piercing light as to provide their present and future with hope," he once wrote. This humanistic vision was matched by his technical innovation and artistic sensitivity.

His photographs were characterized by high contrast, deep shadows, and innovative composition techniques that drew heavily from film noir aesthetics. Faurer experimented extensively with blur, grain, reflections, and unconventional framing, often employing tight cropping and natural lighting to add psychological depth and complexity to his images. He was particularly masterful at orchestrating scenarios that created psychological atmosphere, sometimes adding elements in the darkroom to enhance the mood of his photographs.

The photographer's fascination with multiple exposures and experimental techniques reached its apex in works like "Accident, New York, N.Y." (1949-1952), which TIME magazine called "one of the great photographs of the postwar years". This double-exposed image shows a boy turning away from a car accident scene with its chalk outline of the victim's body, while simultaneously capturing a wedding party on church steps—creating a meditation on death and continuity, innocence and experience.

Commercial Success and Personal Vision

Despite his artistic ambitions, Faurer maintained a successful commercial career, working for prestigious publications including Vogue, Harper's Bazaar, Mademoiselle, Glamour, Elle, Life, and Look for more than twenty years. He complained that his work at Life involved too much travel and quit in the early 1950s, preferring assignments that allowed him to remain in New York. His fashion work was notable for its psychological depth, bringing the same empathetic eye that characterized his street photography to commercial assignments.

Tragically, most of the prints and negatives from his fashion career have been lost—stored with a friend when Faurer left for Europe in the late 1960s and never reclaimed. This loss represents a significant gap in the historical record of mid-century fashion photography, as Faurer's commercial work was highly regarded by his peers and editors.

Recognition and Influence

Although Faurer never achieved the broad public recognition of some contemporaries, his work was deeply respected within the photography community. Edward Steichen, the influential curator and photographer, included Faurer's work in two landmark Museum of Modern Art exhibitions: "In and Out of Focus" (1948) and "The Family of Man" (1955). These inclusions established Faurer as a significant voice in American photography during a crucial period in the medium's development.

Faurer was recognized as a key member of the New York School of street photographers, a loosely defined group that included Diane Arbus, Robert Frank, William Klein, Saul Leiter, Helen Levitt, and others. This group favored candid 35mm photography and sought to capture the psychological undercurrents of urban life, often rejecting the conventions of traditional documentary photography.

Later Years and European Sojourn

In the mid-to-late 1960s, Faurer expanded his artistic practice to include filmmaking, experimenting with hand-held 16mm cameras and filming street life in Manhattan, extending his photographic aesthetic into a cinematic medium. Between 1969 and 1974, he lived and worked abroad, primarily in Paris and London, photographing for European magazines including Elle, Marie Claire, and Vogue.

Upon returning to New York in 1974, Faurer found both the city and himself transformed. He began teaching at numerous institutions, including the Parsons School of Design, Yale University, the University of Virginia, The New School for Social Research, and Stockton State College in New Jersey. His role as an educator allowed him to influence a new generation of photographers during a period when his own production had slowed.

The End of an Era

Faurer's photographic career came to an abrupt end in 1984 when he was struck by a car while running to catch a New York City bus. The serious injuries from this accident prevented him from ever photographing again, marking the conclusion of a career that had spanned nearly five decades. Despite this setback, Faurer lived for another seventeen years, witnessing a growing appreciation for his contribution to American photography.

Posthumous Recognition and Legacy

In the years following his death on March 2, 2001, Faurer's reputation has continued to grow. Major retrospectives have been mounted at institutions including the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston (2002), the Fondation Henri Cartier-Bresson in Paris (2016), and numerous other venues worldwide. His photographs are now held in prestigious collections and continue to influence contemporary photographers.

Faurer's work represents what TIME magazine identified as a crucial "missing link" between Depression-era documentary photography and the more personal, psychologically complex photography that emerged in the 1960s. His ability to capture what he called his "intense desire to record life as I see it, as I feel it" established him as a photographer's photographer—an artist whose influence on his peers often exceeded his public recognition.

Today, Faurer is celebrated as a master chronicler of urban psychology, a photographer who found extraordinary moments of beauty and meaning in the ordinary interactions of city life. His images continue to resonate because they capture something timeless about the human condition: the capacity for grace and dignity even in circumstances of solitude and uncertainty. As he once reflected: "As long as I'm amazed and astonished, as long as I feel that events, messages, expressions and movements are all shot through with the miraculous, I'll feel filled with the certainty I need to keep going".

Louis Faurer's legacy endures not merely as a documenter of a vanished New York, but as an artist who understood that the most profound human truths are often found in the quiet moments between public gestures—in the shadows and reflections that reveal the inner lives of strangers passing on city streets.