Man Ray was the first. Then came his daughter Faye. The Weimaraners as representations of human qualities: this is where William Wegman began, in 1978. Until the complete transformation of the portrait concept.

Serendipity is the word that continuously surfaces when contemplating William Wegman's work, a term that resonates not merely as a description of aesthetic experience but as a guiding principle of creative practice. In Wegman's photographs, serendipity manifests first and foremost in the agency—might it be that we still lack a term that, like agencement/agency, identifies the power of the subject, even if non-human, to "act" in creative contexts?—of his canine collaborators, co-creators of every composition, challenging conventional hierarchies between subject and author.

His trajectory too is serendipitous. "I went to art school, studied painting, and obtained a degree and then a master's. Many artists pursued the second degree because it kept them away from Vietnam War recruitment; it was an exemption. By the mid-sixties, painting was truly being questioned and declared dead." Yet painting, rather than limiting, opened perspectives beyond canvas. "I became interested in performance at the University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana. There was an extraordinary music school, and I worked with John Cage and other composers on interactive projects. I even received a scholarship from the Electronic Engineering Department to explore cybernetics and create interactive environments. By 1966, I was as far as possible from painting. Then I taught at the University of Wisconsin, creating outdoor works, environmental art, and performance actions. I borrowed a friend's camera to document these actions—throwing radios off rooftops, reorganizing library furniture. A friend, the artist Robert Cummings, said to me: Bill, why don't you buy your own camera? So I did. At that time, I was also making videos and television broadcasts: I wanted to reach the public this way, more than through museums. With photography, it worked. By 1970, I was already showing in galleries in Paris and Düsseldorf, a year later in New York. Then I started making drawings on A4 sheets.

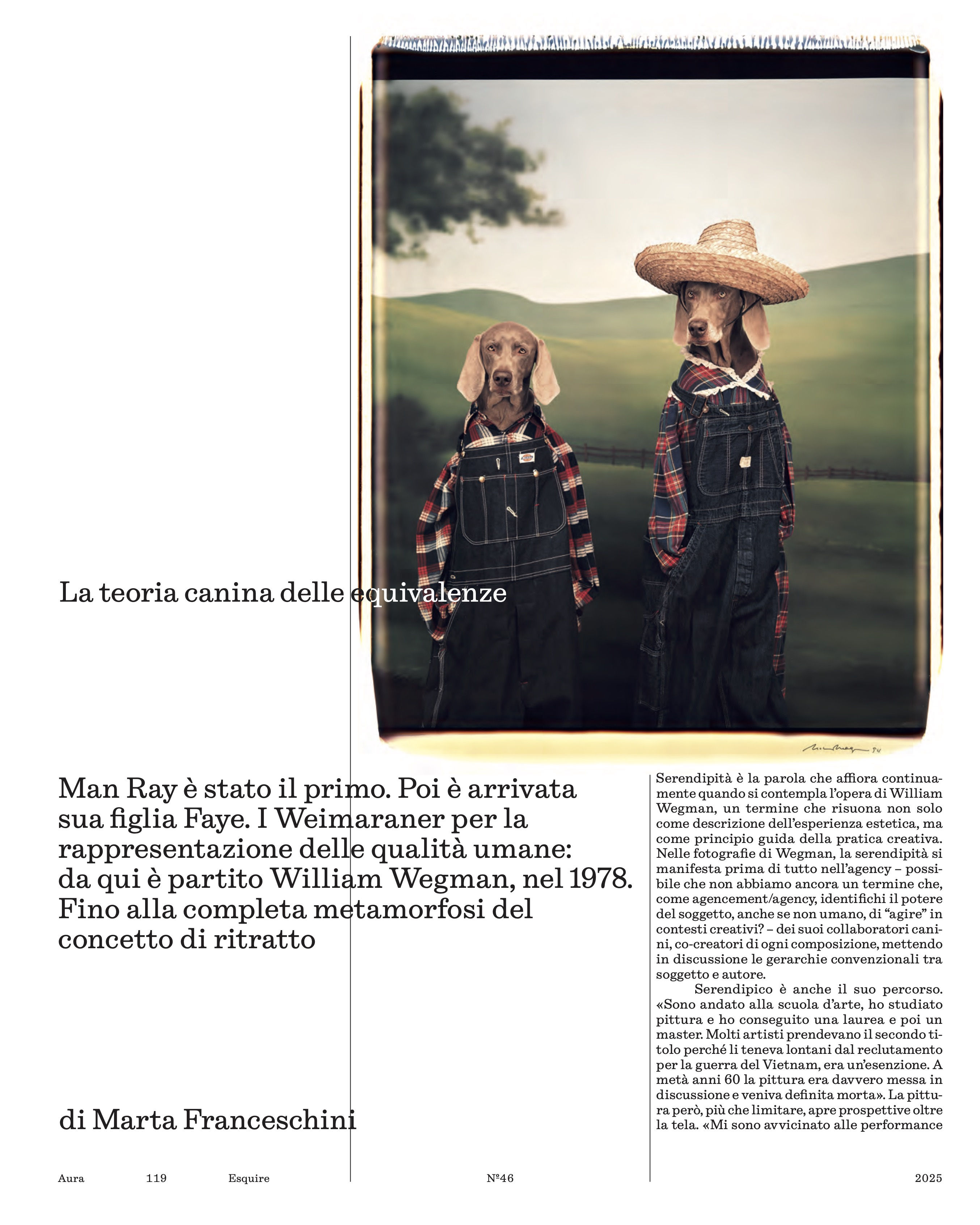

It's the encounter with the Polaroid 20x24 that transforms Wegman's practice. "I used it for the first time in 1978 and it changed everything. It was in color, much larger than 11x14. As a subject, I had my dog, a Weimaraner named Man Ray, and whatever was at hand. The vertical camera required me to position the dog on pedestals or tables, training him to react to the lens, and this completely transformed my approach."

Wegman's practice evolves further, this time through the subject: Faye Ray, daughter of Man Ray. "My assistant Andrea wrapped her in fabric so she wouldn't fall off the stool. She looked like a column. And when Andrea moved her hands from behind, it seemed like Faye had human arms. She was my first anthropomorphic animal. Unsettling and seductive." The unexpected intertwines with composition, and photography becomes theater, narrative. "From there, I was invited to make videos for children on Sesame Street. Suddenly, I was more popular than I deserved to be."

The popularity stems from how directly the images communicate. "The anthropomorphic nature of dogs speaks to human types we encounter in life. And when Faye had puppies, I suddenly found myself with an entire cast—mother, daughter, son, sister, brother—and new narrative possibilities." Recurring characters, from puppies to adult figures, structure the stories: Faye as wicked stepmother, Betty as Cinderella, Penny Candy in multiple roles. Seriality allows exploration of time and relationships between subjects. "There I discovered ways to create expressions: a dog could seem aggressive if I stepped back, or friendly if I moved closer. The camera position and my influence on set determined the outcome." Little planning, but great attention to what happened on set. And knowledge of each subject's temperament (the dogs, almost always his own) to assign the right roles in the story.

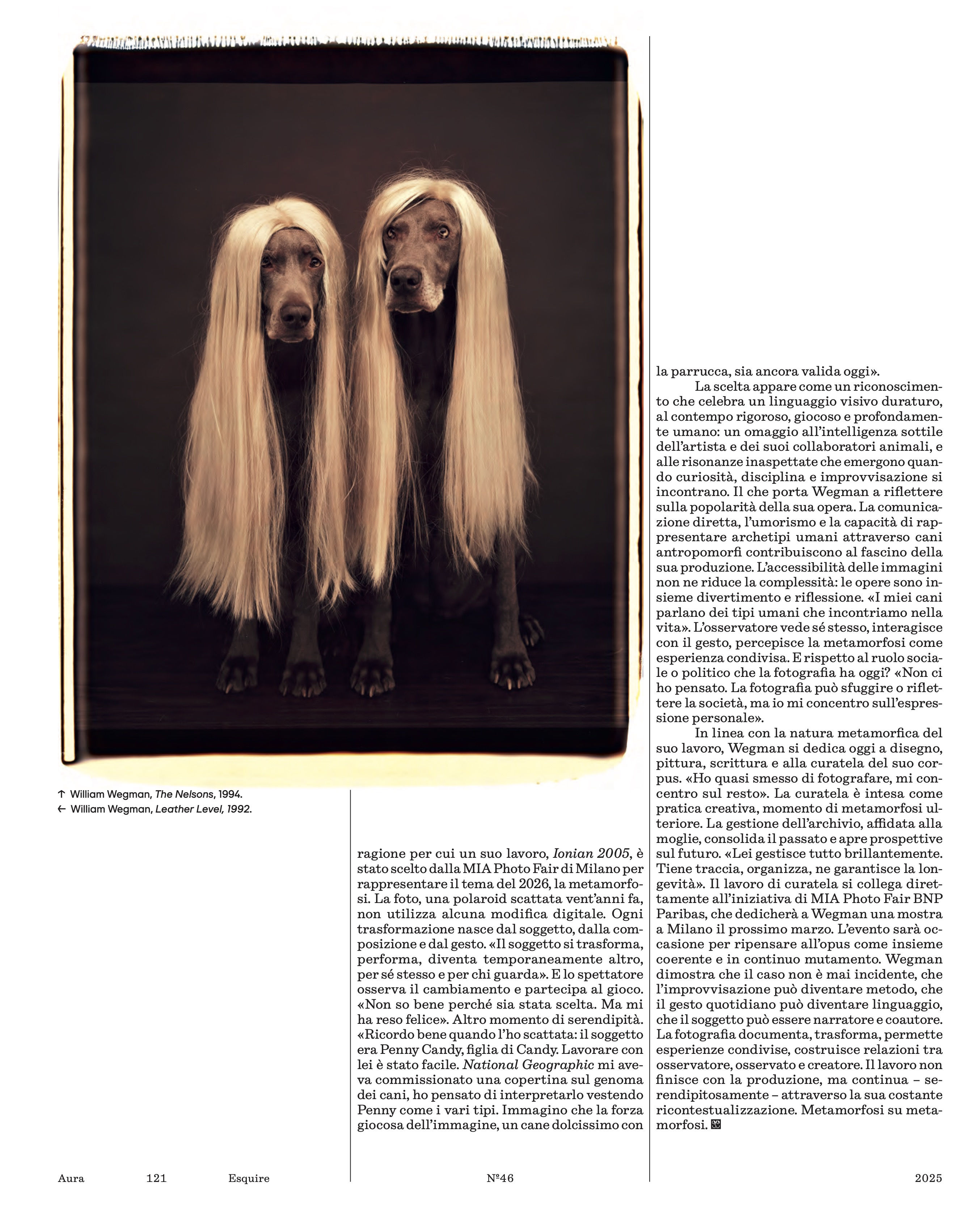

This shared authorship makes Wegman's work naturally evolving—the forms continuously change, subjects transform, and with irony narrate stories suspended between reality and imagination. This is why one of his works, Ionian 2005, was selected by Milan's MIA Photo Fair to represent the 2026 theme of metamorphosis. The photograph, a Polaroid shot twenty years ago, uses no digital manipulation. Every transformation emerges from the subject, from composition and gesture. "The subject transforms, performs, becomes temporarily other, for itself and for the viewer." And the spectator observes the change and participates in the game. "I'm not entirely sure why it was chosen. But it made me happy." Another moment of serendipity. "I remember well when I shot it: the subject was Penny Candy, daughter of Candy. Working with her was easy. National Geographic had commissioned me to do a cover about the canine genome, so I thought to interpret it by dressing Penny in different types. I imagine the playful force of the image, a sweet dog in a wig, is still valid today."

The selection appears as recognition celebrating a visual language that is enduring, rigorous, playful, and profoundly human: a tribute to the subtle intelligence of the artist and his animal collaborators, and to the unexpected resonances that emerge when curiosity, discipline, and improvisation meet. This leads Wegman to reflect on the popularity of his work. Direct communication, humor, and the ability to represent human archetypes through anthropomorphic dogs contribute to the appeal of his production. The accessibility of the images does not diminish their complexity: the works are simultaneously entertainment and reflection. "My dogs speak to the human types we encounter in life." The observer sees himself, interacts with the gesture, perceives metamorphosis as a shared experience. And regarding the social or political role photography has today? "I haven't thought about it. Photography can escape or reflect society, but I focus on personal expression."

In line with the metamorphic nature of his work, Wegman today dedicates himself to drawing, painting, writing, and curating his corpus. "I've almost stopped photographing, I focus on the rest." Curation is understood as creative practice, another moment of metamorphosis. The management of the archive, entrusted to his wife, consolidates the past and opens perspectives for the future. "She manages everything brilliantly. She keeps track, organizes, ensures its longevity." The curatorial work connects directly to the MIA Photo Fair BNP Paribas initiative, which will dedicate an exhibition to Wegman in Milan next March. The event will be an opportunity to reconsider the opus as a coherent whole in constant flux. Wegman demonstrates that chance is never accident, that improvisation can become method, that the everyday gesture can become language, that the subject can be both narrator and co-author.

Photography documents, transforms, enables shared experiences, constructs relationships between observer, observed, and creator. The work does not end with production but continues—serendipitously—through its constant recontextualization. Metamorphosis upon metamorphosis.

CREDITS:

Editor in Chief: Giovanni Audiffredi

Text: Marta Franceschini

Photo: Courtesy William Wegman and Galeria Alta, Andorra

Art Direction: Tomo Tomo

Editor in Chief: Giovanni Audiffredi

Text: Marta Franceschini

Photo: Courtesy William Wegman and Galeria Alta, Andorra

Art Direction: Tomo Tomo

1

of 91